Conclusion

Pain affects most of us at some time in our lives in one way or another to varying degrees. It brings attention to the fact that we are not perfect, and that we are vulnerable. The experience of pain, either through illness or injury, is very much a part of our lived experience and is also a sign that we are alive.

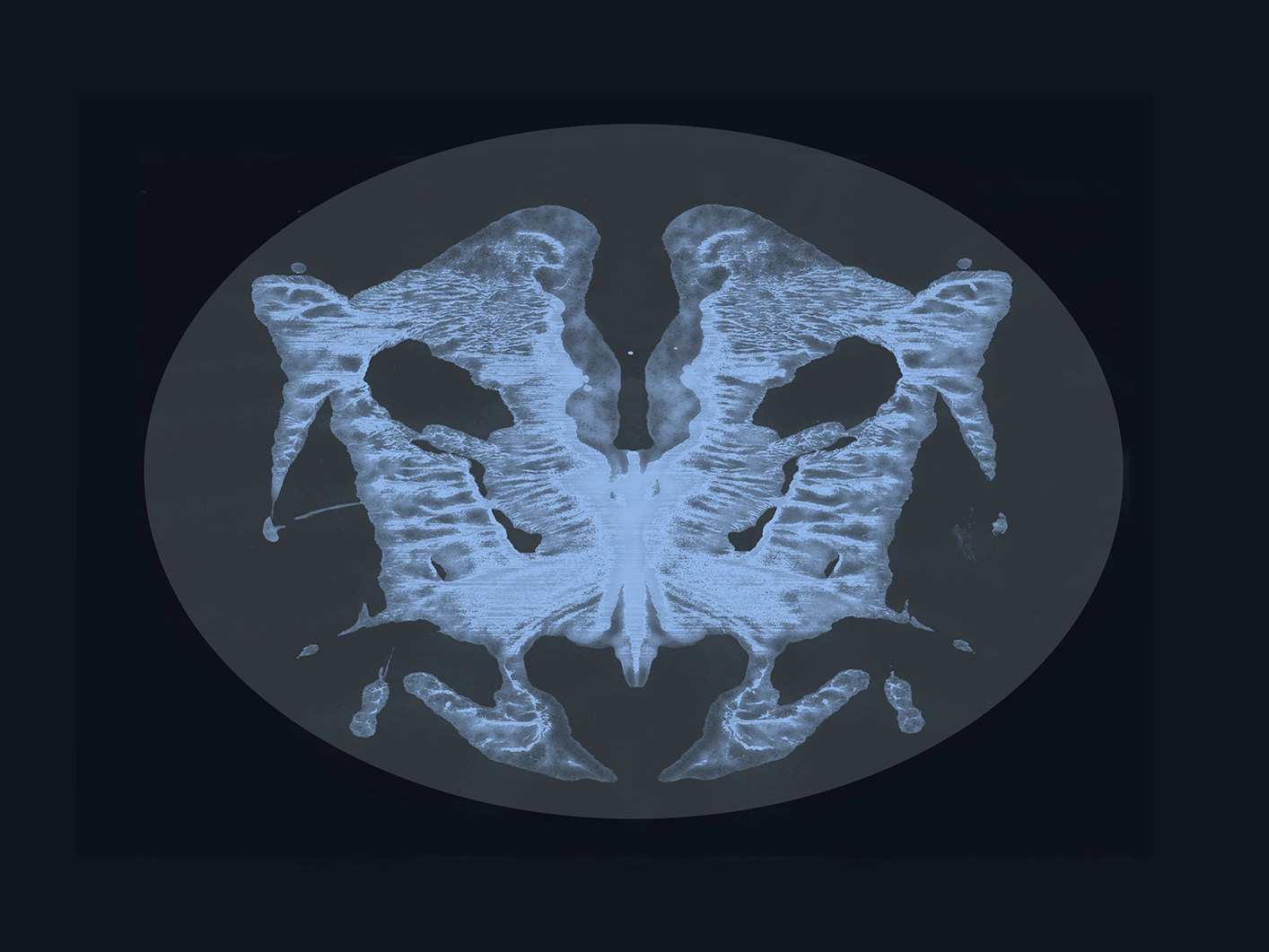

The subjective nature of pain makes it difficult for a third party to understand its complexity. Pain is invisible, and directly trying to communicate this ambiguous yet fundamental perception can often add to the burden for the person living with it. The negative effects of illness span all aspects of our lives, not just the physical. In order to treat chronic illness and pain, it becomes necessary to address this multi-layered trait. Thus, Hegel’s position on the importance of treating a person with illness as a whole is still relevant today.

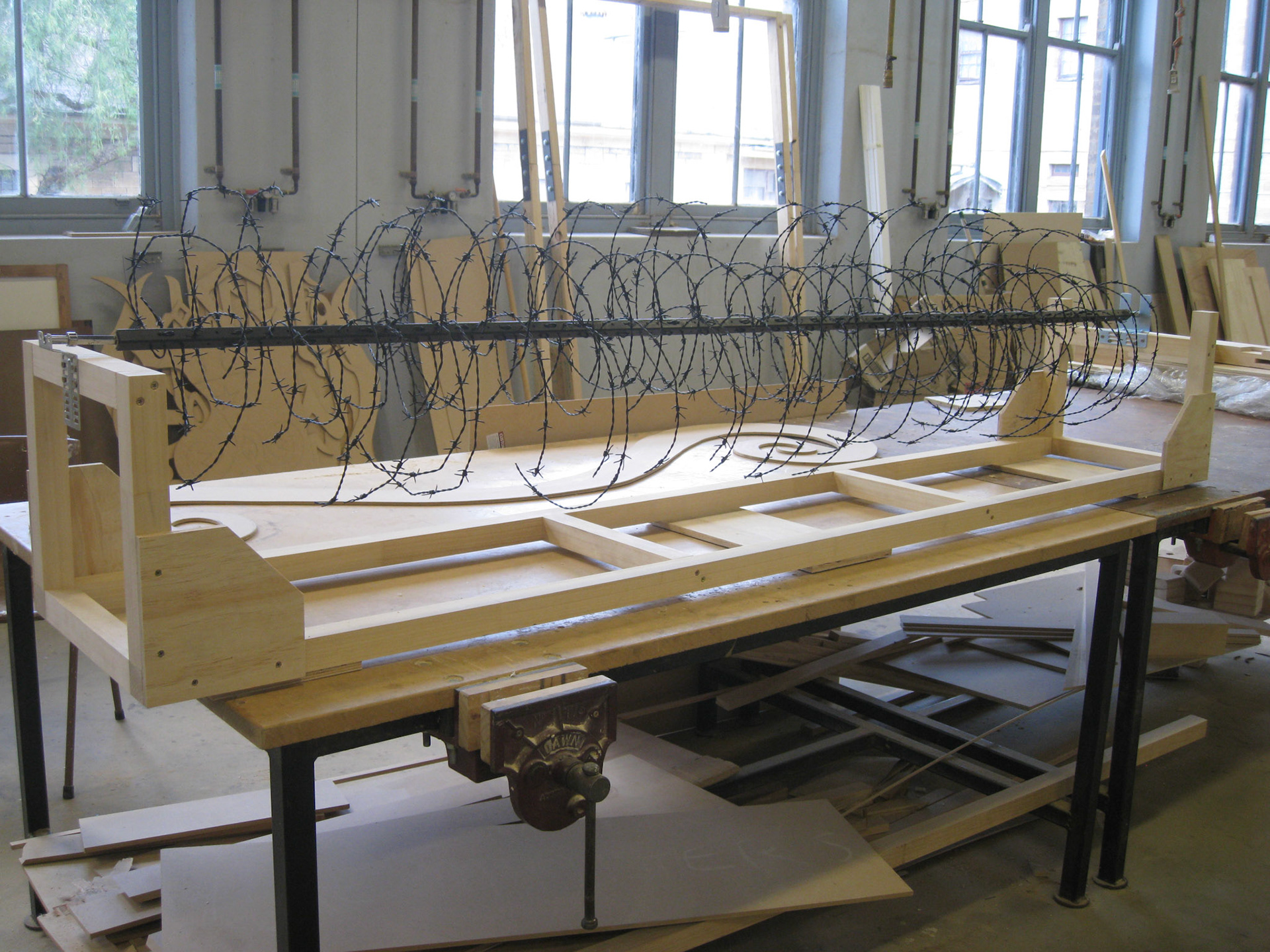

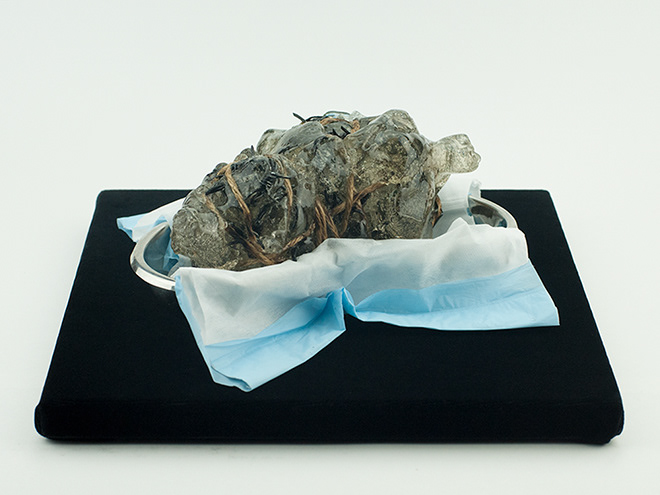

Fortunately, pain researchers in recent years have acknowledged the fact that each individual experiences pain differently. Perception of pain is no longer believed to be always symptomatic of a physiological disease or injury that can be located and seen. However, many aspects of pain still leave researchers and medical practitioners baffled, and it is even more difficult for the general public to understand its complex nature. I do not assert that the new theories and praxis of pain can answer all the challenges of communicating one’s pain – as is pointed out through the closed doors and smooth façade of the plexiglass in my installation.

I would like to see both patients and physicians equally present with curiosity and optimism for each pain experience, rather than seeing pain through the lens of the existing social stigma. This idea of collaboration is a surprising outcome of my installation, one I never consciously intended but that I now contemplate with the rhetorical question - what would it look like if we, as individual subjective emotional beings, could co-exist alongside objective medical science?

We are, as interrelated social beings, always by default trying to communicate with others – to connect, adapt, negotiate, and disrupt - even with the clinical façade of the impartial medical system, because behind that facade there are real people.

Amongst the unresponsive solid locked drawers in the installation, the viewing windows provide visual narratives laying bare some of the multifaceted visceral natures of the pain experience. These windows speak the ‘truth’ of one’s lived experience in a way no words could ever replace and are as valid a way of communicating as any scientific pain measurement tool, if not better. Creating these windows was my way of legitimising my experience that could resonate with others.

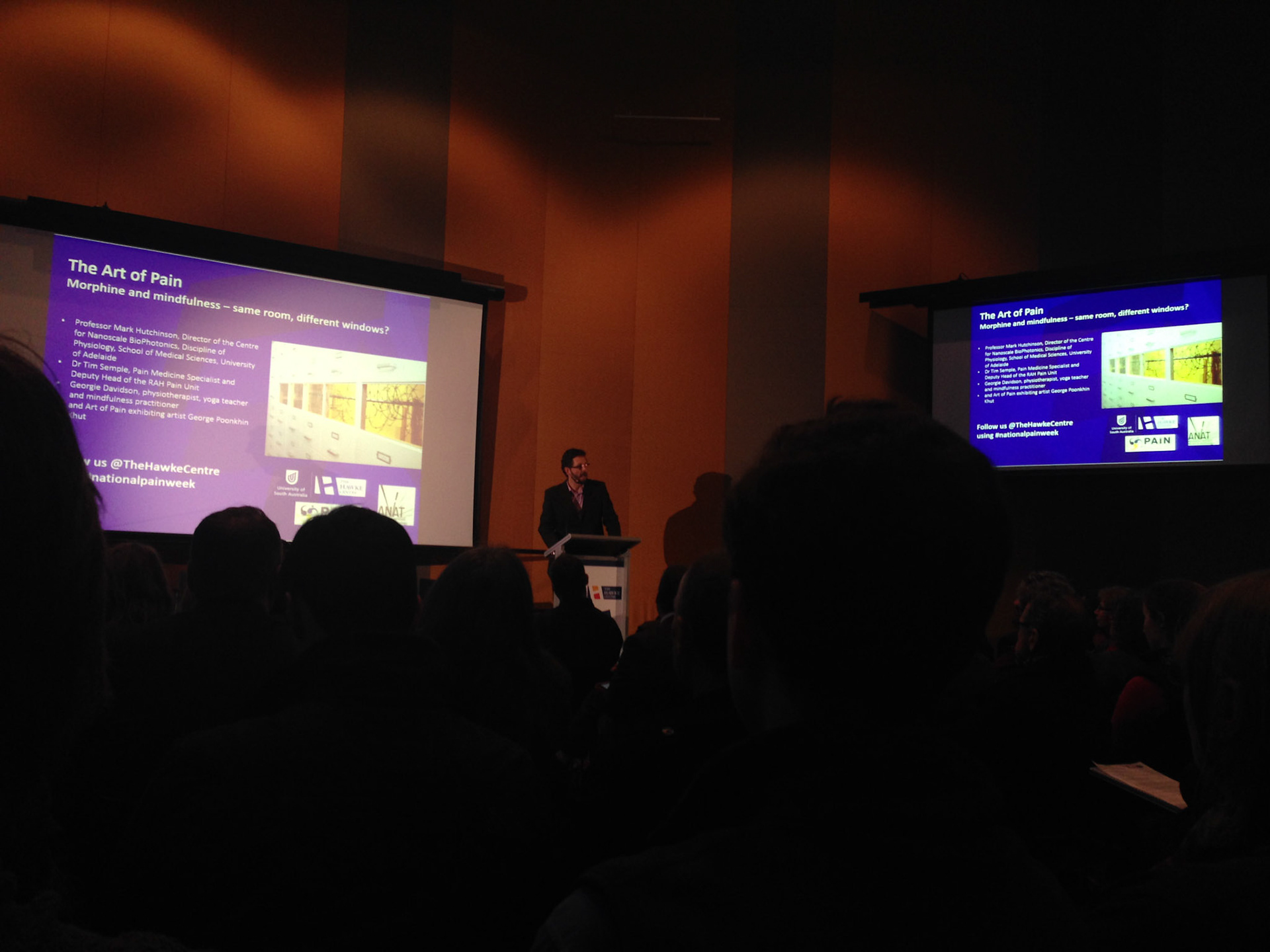

The collaboration focuses on drawing out the emotional connections between people, bypassing the hierarchical structures of the traditional physician and patient relationship.

There is room for art to fill in some of the gaps alongside science, as an alternative storytelling platform, and in allowing the audience to create meaningful relevance and connections with what is essentially an abstract concept. In fact, pain and art have something in common. They both benefit from using metaphorical, visual, and experiential forms to better communicate and share concepts with others. Through this work, I hope to generate a better understanding of the complexities of pain for myself and for the wider audience.